SPECIAL REPORT

H O R S E R A C I N G

RACING BABIES: ARE TWO YEAR OLDS TOO YOUNG?

Written and Researched

by JANE ALLIN

January 2012

INSIDE THIS REPORT

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Stages of Bone Growth in the Horse

Part 3: Effects of Training and Racing on the Immature Musculoskeletal System

Part 4: What Racing People Say: Fact or Fiction?

Part 5: The Verdict: Training Regimens - Too Much, Too Soon?

Part 3: Effects of Training and Racing on the Immature Musculoskeletal System

Although much research has been conducted on the racing of 2-year olds the consensus as to the effects of early training and racing on musculoskeletal and cardiovascular health is anything but resolved.

Although much research has been conducted on the racing of 2-year olds the consensus as to the effects of early training and racing on musculoskeletal and cardiovascular health is anything but resolved.

An Australian study on the rates of injuries that occur during the training and racing of 2-year olds revealed that 85% suffered at least one incident of injury or disease. [1]

Moreover other anecdotal and survey evidence cite a high incidence of breakdowns during the preparation of young horses for 2-year old in-training auctions which elicits concern from an animal welfare perspective. While it is acknowledged that a wealth of factors can contribute to musculoskeletal injury in performance horses the underlying question is whether the musculoskeletal structure is compromised by entering training and racing circuit at such a young age.

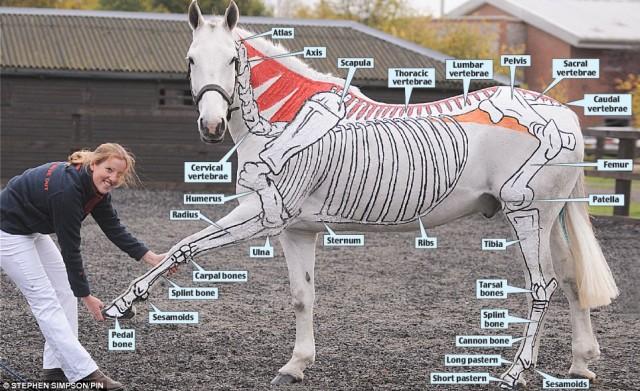

Without question the strength and proper development of the young horse’s musculoskeletal system is paramount to providing soundness and structural support during exercise and racing events.

Furthermore while it is true that the bones of immature horses strengthen in response to exercise there is also scientific evidence that overloading of the bone structures as a result of excessive training in the young Thoroughbred can and does lead to increased bone failure and joint injury. As has been validated time and again, the injury rate and wastage observed amongst two and three year old horses are acutely disproportionate and preeminently musculoskeletal in origin.

For the performance horse the most common musculoskeletal injuries involve tendon and ligament damage, stress and chip fractures as well as strains placed upon the joints and foot soreness. While the manner in which a young horse is trained and raised for competition has a profound influence on their strength and future soundness, ultimately the severity of any injury is unequivocally associated with the type of training and the physical demands the horse is subject to.

In view of the fact that introduction to the race track for the majority of Thoroughbreds begins at the age of two, most will embark on a training schedule between the ages of 15 and 20 months depending on the month in which they were born. [2]

The disparity in the age at which these young horses begin their training in North America is a result of the standardization of racing ages stipulated by the American Jockey Club wherein the established birth date for all horses, regardless of the actual foaling date, is January 01.

Apart from the fact that the older horses starting in the same calendar year have a decided advantage on the race track, the maturation rate of growth plates in all of these horses is in the early development phase which begets a profusion of lower-limb ailments and injuries.

The high incidence of unsoundness in the young racehorse has been conclusively linked to overloading of, and excessive concussive forces on the bone structures, the age at which training begins, the speed at which the horse is worked, as well as the ability of the bone and joint structures to adapt as the horse increases in weight and loading forces upon the limbs become more demanding. [3]

Undeniably exercise contributes to robust skeletal development through the process of “bone remodeling”, a process in which bones increase in strength and bone mass, however it is critical to acknowledge that this is a slow process. In cases where training takes place during the bone growth phase, such as in young Thoroughbreds, this remodeling process can take up to four months for completion, predisposing the horse to increased risk of career-limiting injury particularly if the training regimen is too aggressive. [4]

Of particular note is that the remodeling of bone in response to exercise does not result in superior quality bone. Bone remodeling is a continuous repair process that occurs in response to physio-chemical factors such as stress from exercise and repair during injury, for example. [5] During the process of remodeling, bone is removed from a particular location on the surface followed by formation of new bone at the same site which eventually strengthens through the addition of calcium and phosphorous (i.e. mineralized). [6]

By way of increased loading during exercise bones gradually become stronger and denser however the exercise regimen must be well controlled. When repetitive stresses routinely exceed the ability of the bone forming cells (i.e. osteoblasts) to sustain adequate metabolic activity in response to the demands of rigorous loading schedules an increased risk of fatigue or “stress” fractures is inevitable. [7]

Stress fractures are all too commonly observed in young racehorses as a result of repetitive overloading of the immature musculoskeletal system where many trainers have disregarded the required gradual strengthening phase prior to the return of grueling training or racing sessions.

As several studies in a number of countries have illustrated, the most common cause of “wastage” in 2-year olds in training is dorsal metacarpal disease (DMD), more commonly referred to as shin soreness or “bucked shins”.

Technically bucked shins are bilateral fatigue fractures of the third metacarpal bones. While some investigations have reported shin soreness to occur in as many as 90% of 2-year old Thoroughbreds in race training, other estimates are for the most part lower (20% - 70%) principally as a result of geographic location where training methodologies can vary substantially. [8], [9]

This painful forelimb affliction is characterized by temporary lameness and localized soreness over the dorsal cortex of the third metacarpal bones accompanied by swelling and a reluctance to work at speed. [10]

While many trainers believe that the development of bucked shins is a prerequisite for toughening the young Thoroughbred’s cannon bones this is certainly not the case, particularly in the US, Australia and New Zealand where 2-YO racing is more prevalent and dirt tracks prevail. In fact, the exact opposite is true; this condition is a symptom of acute and continuous overloading during workouts where the bone is incapable of responding quickly enough for normal repair to occur.

“Bucked shins (also known as "shin soreness") can also be regarded as bone modeling gone wrong (see X ray on page 86). This painful condition is extremely common in young racing Thoroughbreds and Quarter Horses (and occasionally Standardbreds) worldwide. As expected, with the onset of galloping exercise, additional bone is deposited on the front portion of the cannon bone--which should ultimately result in improved bone strength. However, early on this new bone appears to be prone to microfractures similar to the stress fractures that can occur in human athletes during training.” [11]

In other words, this is abnormal bone growth resulting from cyclic limb overloading which ultimately questions the ability of 2-year old Thoroughbreds to adapt adequately to the rigors of training and racing.

Additionally, this condition is not restricted to 2-year olds but also occurs regularly in 3-year olds. [12] By the age of four and older however bucked shins are not a common occurrence further suggesting a casual relationship between the high incidence of injury and wastage rates observed in the population of young racehorses and the stage of development of their immature bones.

Of particular relevance in terms of the incidence of bucked shins is the type of track and training regimen the young horse is exposed to.

“Surveys indicate that the risk of metacarpal remodeling in horses (and greyhounds) is influenced by the track surface (moisture content and compaction) and design (banking and length of straight gallop), radius and crossfall of bends and end circles, seasonal conditions and the speed and distance of fast exercise in the training program (Ireland, 1998; Bailey, 1998; Table 1).” [13]

As shown in Table 3, there is a profound difference in the incidence of DMD when a more forgiving surface (e.g. turf), longer pre-race preparation and wide radius and straight line gallops are employed in lieu of hard dirt, tight radius turns and insufficient race preparation as is typical in the US and Australia.

TABLE 3.

Incidence and reasons for occurrence of dorsal metacarpal disease

in the UK, US and Australia [14]

| United Kingdom | Soft training surfaces, on peat moor areas, straight line gallops, long pre-race preparations (12-14 weeks) – low risk of bone strain and adequate time to adapt. | |

| United States | Dirt tracks, some banking and tight end circles, 10-12 weeks ace preparation – increased bone stress and less time to adapt. | |

| Australia | In Australia, most horses are trained on circle racetracks. Dry hard track surfaces, small radius bend(s) in tracks, no banking, 8-10 weeks race preparation – high risk of bone strain and overload, little time to adapt to racing speed with a too-fast-too-early program. |

In Australia, most horses are trained on circle racetracks. Dry hard track surfaces, small radius bend(s) in tracks, no banking, 8-10 weeks race preparation – high risk of bone strain and overload, little time to adapt to racing speed with a too-fast-too-early program

Clearly the training methods typical of the UK promote gradual incremental loading of the bone at controlled strain loads that allow remodeling to occur at a defined pace with more time to adapt to racing speeds.

“If a horse is pushed too fast too early, the stress loading on the immature bone stimulates emergency modeling with deposition of weaker fibrous elastic bone to reinforce the bone so that it can withstand the forces of galloping.” [15]

Without a proper training schedule to permit controlled remodeling, the rate of new bone growth cannot be sustained in response to exercise meaning that when the bone is loaded there is a high risk of fracture. This is clearly observed for the North American and Australian methodologies where, at the extreme, the incidence of bucked shins can be as much as eight times as high (i.e. - 10% in the UK versus - 80% in Australia) Apart from bucked shins, this further suggests that the large difference in injury and breakdown rates observed between the UK, for example, and North America can be attributed to the unnecessary rigorousness of NA training regimens.

However bucked shins are by no means the only injury that plagues the young horse; a plethora of other ailments arise that can lead to debilitating problems ranging from joint, tendon and other musculoskeletal issues to cardiovascular degeneration.

Several studies have indicated that overly strenuous exercise in the 2-year old horse may contribute to the development of chronic degenerative joint disorders. One such undertaking endeavored to correlate the effect of persistent exercise with changes at the molecular level in the articular cartilage of the joints.

Results of this research supported the premise that characteristic training regimes are sufficient enough to trigger a disturbance in the physiological and biochemical development of the collagen network in a joint. [16] In essence, this disruption in collagen formation was found to have the potential of initiating micro-damage as evidenced by lesions and wear and tear lines on the proximal phalanx of the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint, ultimately a predisposing factor to the development of degenerative joint disease. [17]

Yet another study regarding the integrity of the fetlock joint (i.e. the MCP) examined the relationship of the high incidence of injuries to the soft tissues and joints in the distal forelimbs observed in 2-year old horses and the immature musculoskeletal structure as a function of joint stiffness and shock absorption.

Statistical analysis of the data based on the “dorsi-flexion” - backward bending of the fetlock joint – suggested that the tissues and skeletal structure supporting the forelimbs of 2-year old Thoroughbred horses are not sufficiently mature to withstand the cyclic strain experience during race training. [18]

What this study demonstrated was the comparably lower stiffness in the suspensory apparatus tissues in younger horses which is believed to be associated with a measurable decrease in shock absorption ability relative to older Thoroughbreds. Reduced shock absorption will have the effect of increasing the degree and rate of limb loading in the 2-year old horse. As a result of alteration of the material and mechanical properties of bone in response to overloading, the bones become more brittle and less stiff thereby predisposing the immature musculoskeletal structure to increased risk of fatigue fractures in consequence of the greater bending loads imposed upon the forelimbs. [19]

“In conclusion, forelimb injuries have been shown to decrease with age, maturation, adaptive bone remodeling and adaptation through exercise which all serve to increase the stiffness and toughness of skeletal tissues……Our findings suggest that 2-year old Thoroughbreds may be too immature to train safely according to traditional regimens.” [20]

Tendon and ligament injuries also tend to be a widespread cause of lameness in 2-year old performance horses as a result of inappropriate training or excessive work. One such common condition that afflicts the young Thoroughbred is the development of “bowed tendons”. A bowed tendon (tendonitis) can be described as follows:

"Each tendon is an elastic belt made of thousands of individual fibers, and damage may range from the rupture of only a few tendon fibers to the rupture of the entire tendon. Bleeding from severed fibers into the interior of the tendon causes the tendon to swell. As a digital tendon swells, it bows outward behind the cannon bone--hence the term bowed tendon.” [21]

The broad-spectrum cause of this condition in the young horse can be ascribed to severe strain induced by disproportionate loading of the immature musculoskeletal structure. A bowed tendon is a devastating injury which requires long periods of rest typically anywhere from 6 months to a year and as a rule less than 50% of horses suffering from this condition return to the track to resume successful careers. [22]

While the pivotal concern of racing 2-year olds is focused on the robustness of the musculoskeletal system, the cardiovascular, respiratory and gastrointestinal health of the young Thoroughbred is also challenged by the rigors of established training programs according to the literature (e.g. atrioventricular valvular regurgitation, pulmonary bleeding, gastric ulceration). The results of this research together with myriad anecdotal evidence of other afflictions precipitated by imprudent training and racing schedules are by and large suggestive of exploitation in the name of profit at the expense of the horse.

Nonetheless, regardless of what opposing delegates of the argument value in the assessment of whether racing should begin at the tender age of two, what seems fundamental in determining the consequences of traditional training schedules is the wear and tear on the overall immature circumstance of 2-year old horses and the need for a viable and honest assessment of the capacity to tolerate the unwarranted demands put upon them to perform.

_________________________

[1] http://kb.rspca.org.au/What-is-the-RSPCA-position-on-racing-two-year-old-horses_376.html

[2] http://vip.vetsci.usyd.edu.au/contentUpload/content_2713/Sullivan.pdf; http://www.thehorse.com/ViewArticle.aspx?ID=72

[3] http://en.engormix.com/MA-equines/health/articles/bone-biomechanics-review-influences-t311/p0.htm

[4] Ibid.

[5] http://www.eurekalert.org/features/doe/2003-04/danl-mbr041603.php

[6] http://www.thehorse.com/ViewArticle.aspx?ID=3673

[7] http://www.healthehoof.com/bone_remodeling_equine_limb.html

[8] http://animalscience.tamu.edu/images/pdf/equine/equine-scientific-principles.pdf

[9] http://igitur-archive.library.uu.nl/student-theses/2009-0225-201822/UUindex.html

[10] http://www.wfu.edu/~rossma/Fetlock.pdf

[11] http://www.thehorse.com/ViewArticle.aspx?ID=3673

[12] http://vip.vetsci.usyd.edu.au/contentUpload/content_2713/Sullivan.pdf

[13] http://en.engormix.com/MA-equines/health/articles/bone-biomechanics-review-influences-t311/p0.htm

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] http://vip.vetsci.usyd.edu.au/contentUpload/content_2701/Reed.pdf

[17] Ibid.

[18] http://www.wfu.edu/~rossma/Fetlock.pdf

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] http://www.thehorse.com/viewarticle.aspx?ID=3426

[22] http://itoba.com/vetinjuries2.html

Continue reading . . .

Part 1: Introduction | Part 2: Stages of Bone Growth in the Horse | Part 3: Effects of Training and Racing on the Immature Musculoskeletal System | Part 4: What Racing People Say: Fact or Fiction? | Part 5: The Verdict: Training Regimens - Too Much, Too Soon?