SPECIAL REPORT

H O R S E R A C I N G

RACING BABIES: ARE TWO YEAR OLDS TOO YOUNG?

Written and Researched

by JANE ALLIN

January 2012

INSIDE THIS REPORT

Part 1: Introduction

Part 2: Stages of Bone Growth in the Horse

Part 3: Effects of Training and Racing on the Immature Musculoskeletal System

Part 4: What Racing People Say: Fact or Fiction?

Part 5: The Verdict: Training Regimens - Too Much, Too Soon?

PHOTO CREDIT

Gerald Marella

FineARTAmerica

Part 2: Stages of Bone Growth in the Horse

IN ITSELF, the racing industry is a perilous one for the athlete – the horse and the requirement of exceedingly unyielding solicitation of unsurpassed performance excellence. After all, the expenditure is not trivial and monetary losses incurred can be devastating even to the wealthiest of those who endeavor to invest in this business enterprise.

IN ITSELF, the racing industry is a perilous one for the athlete – the horse and the requirement of exceedingly unyielding solicitation of unsurpassed performance excellence. After all, the expenditure is not trivial and monetary losses incurred can be devastating even to the wealthiest of those who endeavor to invest in this business enterprise.

Most notably, horse racing’s most unenviable anathema is the significant incidence of injuries that beleaguer the industry, particularly given that the career of the average racehorse, at best, spans a mere five to six years.

Simply put, the subsistence of a racehorse is a world apart from his expected lifespan.

Moreover, statistics repeatedly reinforce the fact that musculoskeletal injury is by far the most prevalent derivation of what the racing industry terms “wastage” – an idiom used to characterize losses that occur as a result of the training and racing of a horse.

“A number of studies have shown that musculoskeletal injury is by far the most common reason for wastage. In fact, the statistics are staggering -- for example, a study of 314 Thoroughbreds in Newmarket, England, found that lameness was the single most important reason for wastage in young horses in training. More than half of those horses experienced a period of lameness, and in about 20% of affected horses, lameness was severe enough to prevent racing during the period of investigation.” [1]

While there are a host of reasons that can and do contribute to lameness in the Thoroughbred, predominantly as a result of the inherent rigors of such a demanding sport, there is undeniably the question of whether this arises from the unrelenting demands foist upon the young horse and the potentially harmful effects of intensive training on an immature skeletal structure.

One of the most widely-read factual articles regarding the timing and rate of skeletal maturation in horses is referred to as “The Ranger Piece”, courtesy of the Equine Studies Institute (ESI) which can be found here. [2] What this article clearly communicates is the fact that the vast majority of horses, particularly in North America, begin their racing careers well before they have physically matured.

“…..bottom line – is that no horse, of any breed, in any country, at any time in history, either now or in the past, has ever been physically mature before it is five and a half years old; and that would be small scrubby mares living on rough tucker. Healthy domestically-raised males, and many females, do not mature until they are six. Tall, long-necked horses may take even longer than that.” [3]

The long bones of a horse develop from cartilage by a process known as ossification or simply “bone formation” both at the center (diaphysis) and ends (epiphysis) of the future bone.

Situated between these two regions is a (metaphyseal) growth plate which permits the lengthening of the long bones as the foal grows. Additionally there is a second growth plate (epiphyseal) that forms as the ossification at the ends of the bone (epiphysis) advances outward effectively becoming the articular surface of the joint. [4]

Figure 1. Parts of a Long Bone

http://www.worldscibooks.com/etextbook/5695/5695_chap01.pdf

Figure 2. Bone Growth (Endochondral Ossification)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bone

What is important to recognize is that, apart from the skull, these growth plates are present in every bone in the skeletal structure of the horse (in some cases multiple plates exist, for example in the spine) wherein conversion to bone takes place at different rates in more or less a “bottom-up” progression beginning with the wedge-shaped coffin bone encased in the hoof.

Ascending from the coffin bone, which is fused at birth, up to and including the small bones of the knee requires between 1 ½ to 2 ½ years for complete ossification to take place.

From here upwards and finally to the spinal column - comprised of 32 vertebrae with multiple growth plates and the last to fuse - the conversion process takes a minimum of 5 ½ years depending on the size and sex of the horse.

As a general rule the larger the horse, the longer the time required for ossification where it is possible in some cases for horses not to reach full maturity until the age of 8. [5]

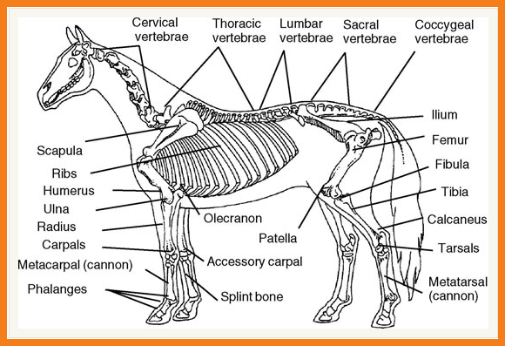

Figure

3. Skeletal System of the Horse -

The horse's body is made up of 216

bones.

The forelegs carry as much as 60 percent of the weight of the

horse.

http://www.netplaces.com/horse/horse-anatomy/the-skeletal-system.htm

Clearly the process of conversion of growth plates to bone takes time; at the age of two the plates in the knees for many of these horses will still not be fully fused, nor will any of the skeletal structure above this location. Moreover even when the conversion to bone is complete and the bone reaches its maximum length this does not imply that its absolute width and cross-section has been attained.

What then, if any, is the correlation between the rate of bone conversion and the high incidence of musculoskeletal injuries and attrition rate in young horses?

Given the demands imposed upon these adolescents during arduous training sessions and racing events an underlying causal relationship seems a rational hypothesis. And exactly how unremitting are the drills they are taxed with?

“The highest weight loading is imposed on the bone structure of the front limbs of racing Thoroughbreds when cornering at the gallop at speeds of up to 15 meters/second (Bailey, 1998). Studies have shown that loading forces on the front limbs of up to twice that of a horse’s bodyweight are imposed when galloping in a straight line (Lawrence, 2003b). For example, when a horse is galloped around a corner on a racetrack, an estimated combined centrifugal and momentum-related loading force of up to 5-10 times the animal’s body weight is placed on bone and joint structures in the lower limbs (Ireland, 1998).” [6]

This speaks volumes. How judicious is an industry that repeatedly subjects these young race horses, racing at near maximum speed, to such overloading of the forelimbs with the conviction that vulnerability to major debilitating injury is simply part of the “game”?

Unfortunately, the answer is not straightforward and, as with all horse racing “topics”, entwined in the pervasive mêlée between the racing contingent and those on the opposing side of the argument.

_________________________

[1] http://www.thehorse.com/ViewArticle.aspx?ID=72

[2] http://www.equinestudies.org/ranger_2008/ranger_piece_2008_pdf1.pdf

[3] Ibid.

[4] http://www.equineortho.colostate.edu/questions/dod.htm

[5] http://www.equinestudies.org/ranger_2008/ranger_piece_2008_pdf1.pdf

[6] http://en.engormix.com/MA-equines/health/articles/bone-biomechanics-review-influences-t311/p0.htm

continue reading . . .

Part 1: Introduction | Part 2: Stages of Bone Growth in the Horse | Part 3: Effects of Training and Racing on the Immature Musculoskeletal System | Part 4: What Racing People Say: Fact or Fiction? | Part 5: The Verdict: Training Regimens - Too Much, Too Soon?